Roy Villevoye

Summer/Fall 1999

Roy Villevoye stayed in Het Vijfde Seizoen with his wife Fransje Killaars and their daughter Celine.

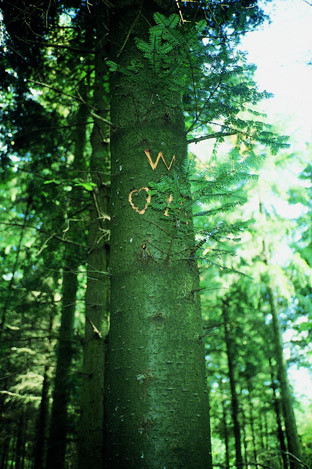

For many years Villevoye’s work has been strongly influenced by his visits to the Asmat area in Indonesian Papua, the former Dutch New Guinea. The Asmat people attribute a great spiritual and emotional importance to trees, out of which they chipped ancestral statues. Villevoye recognizes the therapeutic significance that can be derived from cultivating wood. He asked some patients to carve personal signs in trees in the woods around the grounds. He then documented these signs in the book 'Carving'.

Fransje Killaars became fascinated by the smoking addictions of many clients and counselors. She asked them to collect butts in their individual units. Together with the clients she threaded a giant curtain out of these thousands of cigarette butts, thus creating a collective work of art. She did this by using the same colorful acrylic threads she uses when manufacturing her textile works.

The collective work of art symbolizes the scarce amount of freedom the inhabitants have; a moment for themselves. The ‘curtain’ was exhibited at Het Vijfde Seizoen in 2001 and shown in Galerie De Expeditie in Amsterdam. It is now part of the collection of Het Vijfde Seizoen.

Letter from Roy Villevoye:

Asmat, Papua, december 1998

I’m back with my friends again, in the village of Er. It’s becoming a tradition: a few days on board the dug-out canoe, rowing from Er to the villages upstream. On our way, we always moor at the entrance to Boap’s ‘garden’ - a vast piece of rain forest - which is marked by a few coconut palms. During one of our earlier stops there, we carved our names in some of those palm trees. Now we get a special feeling whenever we return to that remote place and see our names. They have become cherished marks of our personal history there.

Shortly before I left for Asmat, we celebrated the first birthday of our daughter, Céline. The occasion marked the end of an intensely happy year for us. Céline and her mother - Fransje - have stayed at home, in the Netherlands. While I was eating and drinking from the coconuts in Boap’s garden, I felt a sudden urge to carve Céline’s name in one of the palms. Omomã helped me with the tough part. I snapped a few pictures while he was busy carving her name, and when he’d finished, I took a

picture of the result.

Den Dolder, the Netherlands, december 1999

The Dutch foundation Het Vijfde Seizoen (The Fifth Season) invited Fransje and me to stay as summer guests in a pavilion on the grounds of Willem Arntsz Hoeve, a

psychiatric clinic in Den Dolder. In July 1999, Fransje, Céline and I moved in. I had no clear-cut plans as to what I was going to do there, but I had brought a few things with me. Among them were the pictures of Omomá carving Céline’s name, images that have become very precious to us.

The woodland surrounding the pavilion is dense and varied. Pictures taken at the beginning of the twentieth century show the area to be rough heathland, but the heather gradually disappeared after a magnificent stretch of woods was laid out with the help of the clinic’s patients. These woods are now their daily environment, and form a strong contrast with the urban areas where most of them lived.

The summer was sunny and we took many walks in the woods, where we would occasionally spot one or more of the clinic’s residents, either in the distance or

rushing past. What struck me about these woods was the total absence of signs of human presence. Very often, images of my visits to the Asmat lay superimposed - like slides – over our temporary stay in these woods. Here, just like over there, lived

people with a different and personal culture, unknown to us before we came to live here. We became curious and tried to get in touch. The pictures of Omomá carving Céline’s name were unexpectedly helpful. I suggested that the patients should carve a personal sign in one of the trees. This simple, primary act would mark their

presence in the empty woods, the images would link their identity to the place. The images would grow along with the trees, and during their walks in the woods the patients would be confronted with their own images and realise: ‘I am here/I was here’.

The patients’ supervisors enthusiastically helped me to form small groups of patients, and one by one I took the different groups into the woods. The atmosphere was always very pleasant and relaxed, and the woods formed an idyllic setting for the often highly concentrated carvers. As far as I could tell, they enjoyed themselves. They proudly left their work behind to develop into images.

After our stay at Willem Arntsz Hoeve, Het Vijfde Seizoen invited me to develop the material - the slides I had made to document the project - into what has become this book, thus performing, like the carvers in the woods, a personal act. In this way, a spontaneous act - the carving of the name Céline in far away Asmat, the habitat of gifted wood carvers - has generated a kindred piece of work here in the Netherlands. I feel privileged to have had the chance to share, in such a direct way, a new experience with so many patients. It has also left the woods richer in imagery.

Roy Villevoye